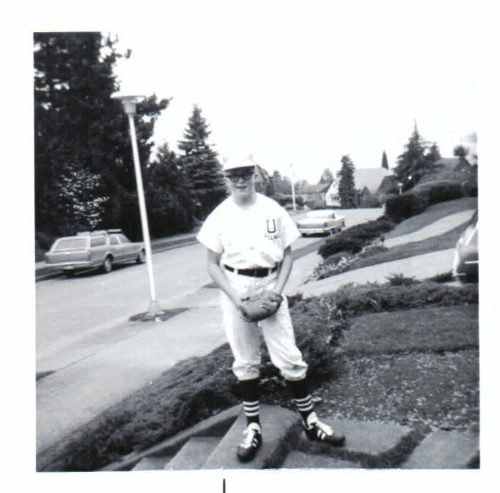

William Walker grew up in Seattle, in ancient days when the Yankees joined him in the living room every Saturday. It was fuzzy black and white, but it was the (only) Game of the Week, when NBC’s Hall of Fame icons Peewee Reese and Dizzy Dean brought us the sights and sounds of summer.

Walker grew up when real gods strode the field, men like Bob Gibson and Frank Robinson and Mickey Mantle and Hank Aaron. Walker was an addict, even before the Seattle Pilots jerked him around, bailed for Milwaukee, and broke his heart. And Walker was 20 by the time the Mariners put their 47-season clown show on the field to cater to shallow fans who love eating garlic fries with their barbecue, and Instagramming pictures of themselves drinking beer with the action behind them…, behind them, for God’s sake. To prove they were there.

Good Lord, turn around and watch the game!

Turn around! Every good and bad thing in life, everything that’s real, everything that matters, is found between those foul lines, in batter’s boxes and dugouts and on-deck circles. Joy, integrity, treachery. Compassion, loyalty, cheating, deceit. Math, physics, and history. Even chemistry. Heartbreak. Redemption. Fairness and kindness. Comedy and tragedy. And foreign languages? Take your pick. Ballplayers, and attentive fans, leave the field more in tune, more experienced, better prepared for what awaits them beyond the ballyard.

Why write a novel mixing this beautiful game, this holy place, with a horrific crime like child sexual abuse? Why go there if, to the best of his knowledge, Walker has never experienced the traumas described in first person in Diamonds and Dirt?

Why? Because we parents want so bad for our kids to be the best. We want it so bad that we let other people do our jobs for us. And that can go tragically wrong.

Walker’s now-adult children spent years on the diamond and in the pool and on the soccer pitch under a dizzying series of coaches. Most were volunteers. Most were tireless, devoted, caring people. A few were out to fulfill some deeper need, some desire for their own glory. They groomed athletes and parents to make it happen, for themselves. They said it was about the kids, but it wasn’t. And boy oh boy, did the moms and dads fall all over themselves to venerate those abusive coaches.

Then Walker saw that dynamic play out again, uglier this time, in a new home town far from where he raised his kids. It was two public, ugly, swim coach departures at the local pool. It was all there: the adoring, obsessed parents; the grooming of entire families; the abuse without consequence; the ostracism of those who stepped out of line; the blubbering hysteria from teenage children when Coach left town. It was all there, and it wasn’t always sexual. But it was always about narcissism and it was always about power.

That’s how Diamonds and Dirt was born. It’s a message to parents to do their damn job, the one job God gave them, and not trust it to anyone else.

Plus, of course, it’s a novel about baseball. And you can’t go wrong with a novel about baseball.

Diamonds and Dirt is Walker’s first novel. The sequel, Tenth Inning, brings Hank back to his old baseball friends as they face a mutual crisis at age 60. Walker really needs a publisher. Meanwhile, he writes poetry and has completed a stage play about courage and character in the face of sex abuse on a college campus, wrapped around the fiftieth anniversary of Title IX.

Walker and his wife of 42 years live on an island near Seattle. Reach him at rubycreekboathouse@gmail.com or 206-940-6269.