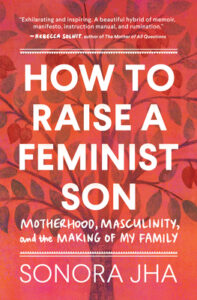

Review: How to Raise a Feminist Son by Sonora Jha, PhD

Sasquatch Press USA, Penguin Random House India, 2021

Goodreads: 4.46 / 5

“Mind if I borrow that opening line?”

Dr. Sonora Jha glanced up at me, taken aback. Clearly this tall old white man, a goofy grin pasted on his face, was oblivious to his own privilege. And he was messing with her.

She was fresh off her keynote speech at a writers’ conference and I was just one among dozens of eager fans who tried to catch her ear as she worked her way out the door. But she paused with a gracious smile.

“Which opening line?”

I felt connected, like I’d found a fellow warrior. “The line about flowers in your hair. ‘Sometimes,’ you said at the beginning of your talk, ‘Sometimes I think everything would be easier if I wore flowers in my hair.’ You said it would be easy to ignore evil, to pretend abuse doesn’t exist. To forget about speaking the truth. Just to be pretty and smile.”

Now she was baffled. I’m practically bald, so how would that work?

“Ummm… why? Flowers in, um, your hair?”

I tried to explain.

“I know what you meant. People want to ignore the hard stuff in my novel. They don’t want to read about what’s real. They want pretty, they want smooth, nice colors and rainbows and butterflies and, well… flowers. They don’t want it ugly… people don’t understand why it’s about, you know… that.”

“What’s your book about?”

“Baseball.”

“Baseball. Really.”

“Yeah. Baseball… baseball and pedophilia. Baseball and manipulation, narcissism, bad parenting, drugs, prison, suicide. It’s about baseball, and it’s about sexual abuse, about trusting precious little children to people we don’t even know, and when they come back to us damaged, abused, crushed, we don’t even believe our own children when they tell us about it…”

“Now that,” Professor Sonora Jha said, “is an important book. Don’t stop until it’s published, and yes you can use that line when you talk about it. And no, don’t ever wear flowers in your hair. It would mean you’ve given up. Besides, Mr…” she glanced at my name tag and gave me a wink… “Besides, William, it wouldn’t be a good look.”

So I haven’t quit. It’s been a couple years since that day. Diamonds and Dirt still isn’t published. I have no publisher, no agent, no editor. But I haven’t quit.

Dr. Sonora Jha, however, has in fact published How to Raise a Feminist Son. It’s a jarring title, not unlike the image of flowers atop a sixtysomething’s shiny white head.

But make no mistake, Sonora Jha wore no flowers in her hair when she wrote this book.

“Why don’t you just cut off his dick instead?” one tweeter tweeted on Twitter in response to the title, even before the book was complete. The timing gave Dr. Jha a chance to include said tweet in the book. Her response is deep and revealing and full of power and grace. And it’s straight-up awesome in its saltiness. And she deserves to have you buy the book and read it there, not here on this page.

Why would she write such a book? To paraphrase, she envisions a world where girls and women can take up the same spaces on equal footing with boys and men, because there’s actually plenty of room for all of us. But the way we raise our boys, the way we keep raising our boys, throws up a giant barrier to that vision. Dr. Jha wants to change that, one feminist son at a time.

She knows what she’s talking about. Her book is a frank and honest memoir of her youth in India and her single motherhood in the USA – and an urgent road map to action for parents to change the world by changing the way we raise our boys.

Dr. Jha even calls out proudly woke Seattle, where she is a journalism professor, for its awkward and clunky feminism. This part rang true for me as it dug deep in the embarrassing legacies of my own home town.

She attempts to understand and connect with women who hate the title’s F word for all its connotations and implications, but who live their own “fiercely feminist” lives – and who could likely read her book and find it challenging and affirming if they could just ignore that one word.

It hasn’t been easy. But as a strong woman with a strong voice, a pen, a keyboard, and a publisher, what’s she supposed to do? Wear flowers in her hair when she could be changing the world? When she could be saving a life? Dr. Jha reminds us of our obligation to do good:

“Can you imagine if Harriet Tubman said ‘Fuck that, I’m tired… I don’t want to be the go-to person?'”

Yeah, that’s kinda my favorite line in the book. Because we live in a world where too many women (one is too many, but still…) agree with Dr. Jha that they’ve been abused, harassed, and molested so often by so many men that they gratefully celebrate those who don’t. Those who keep their comments, and their damn hands, to themselves. “Men of Greatness,” she calls them.

Guys. Come on. That’s a low goddamn bar, isn’t it? We have to do better. Why not start with raising feminist sons?

——————————–

Edit – after posting this, I was excited to receive a reply from Professor Jha with answers to a few questions I sent her. It’s an honor to add those here:

How is your feminist son Gibran feeling now about the things you wrote about him? Is he on board? Does he feel like maybe you over shared here and there?

SJ: Even though he was uncomfortable about a book in which he is the center of the story, he supported me in writing it. He helped with research, with interviews, and he said he wouldn’t read it, so I shouldn’t censor myself. He said he could see how it’s an important book and needs to be out there. That’s my feminist son.

As an old Boy Scout, I felt a chill when you started to tell that Gibran had joined a troop. The scouting experience can run the gamut from harsh to affirming, depending on (among other things) troop leadership. I was relieved to read it was a great experience for him. How do you think scouting affected Gibran’s development as a feminist man?

SJ: I don’t know if scouting directly had an impact on his feminism. The dads who led the scouts in his troop were good, gentle men, and I wrote of them to show that terrible institutions could also have some good men in them and we need to call these men in to work on the feminist enterprise. Of course, individual men as feminists also have to work on dismantling the structures in these institutions that allow abuse and misogyny and homophobia.

You’ve received some super negative feedback on social media, mostly from people who haven’t read the book but don’t like the title. You’ve noted that these messages are “jarring and a bit scary.” Can you elaborate on the extra vulnerability an author experiences when writing on a topic like this? Do you have any regrets?

SJ: No regrets at all. For all the trolling by those afraid of the idea, I’ve received heaps of letters from people who needed the book and also just loved the writing. I am moved by these and hold them close.

The book has been out for about two months. Do you have any “best moments” that you’d like to share? Anything that made you feel particularly gratified for the work you put in?

SJ: Oh, so many lovely reviews and letters and invitations. The thing that’s surprised me most is how many men – not just fathers – have said they’ve loved the book and waited for something like this for so long.

Readers of great authors seem to assume that greatness will be followed by more greatness. What is the next project you’re working on?

SJ: I’m working on a novel and also shaping a new collection of essays.